In the spring of 1968, a young, up and coming filmmaker named George A. Romero set out to craft a horror film and tell a story he was fascinated with telling. In our modern age, things like YouTube or Vimeo allow people to create content and have the opportunity to be seen by millions. But for Romero in 1968, no such platform or success was guaranteed. His directorial debut, Night of the Living Dead was shot without any studio backing, in a single house that was already set to be demolished, and with minimal actors and extras.

All of the odds were stacked against the would-be Godfather of Zombies, a moniker that he had no idea society would eventually bestow upon him. Once the 30 day shoot was complete, and Romero had finished a rough cut of the film, he took the single copy of the reel, threw it into his trunk, and drove from Pittsburgh to New York City in hope of finding anyone who would distribute his film. While on this almost 400 mile trek, Romero heard on the car radio news that would shock the world, and in an unexpected way, affect his film and the success it would soon yield.

The Moment That Shocked The World

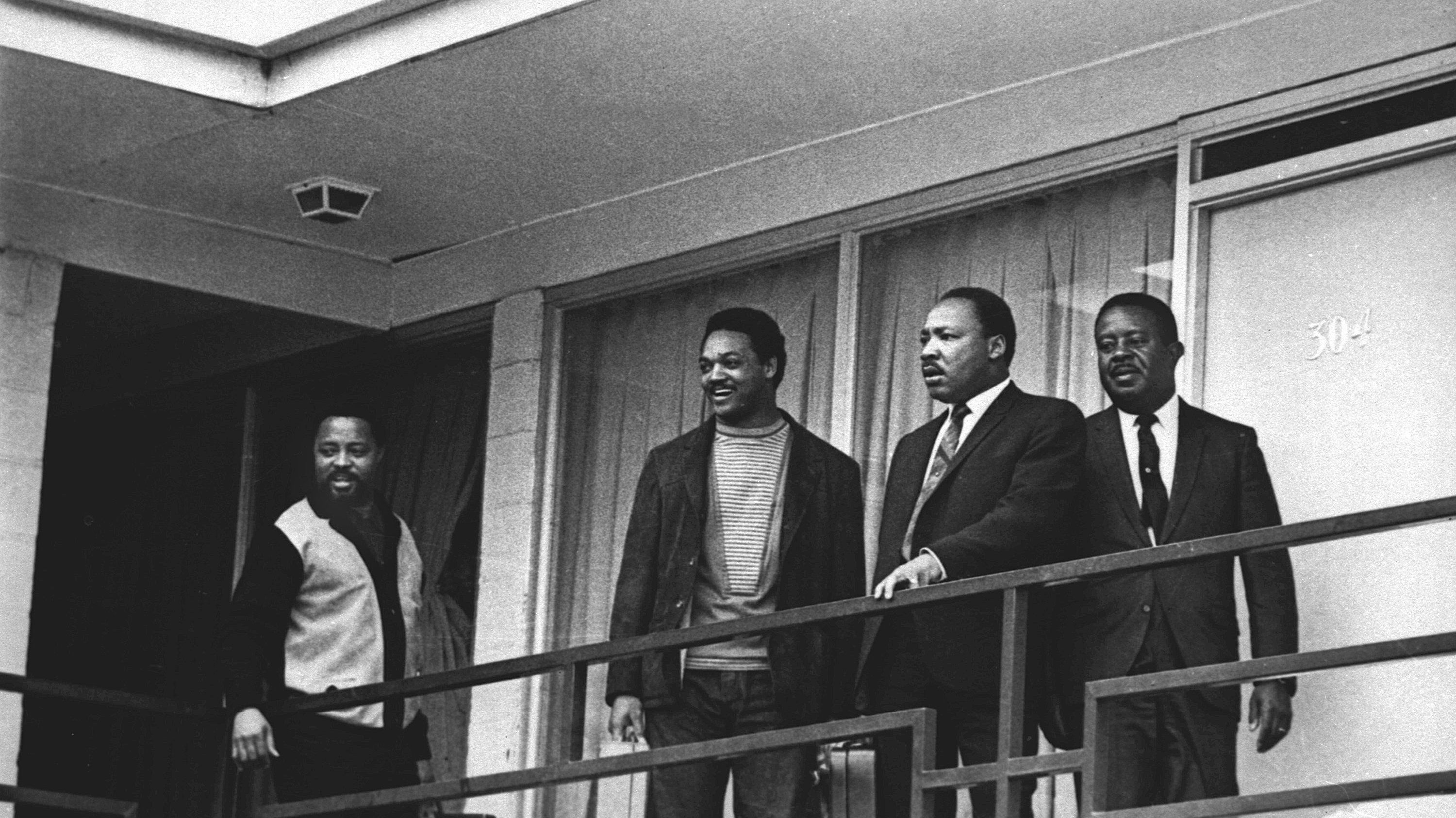

On the night of April 4, 1968, tragedy struck in Memphis, Tennessee when the beloved civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. For years he had been a beacon of hope and an inspiration to millions of people. His morals and teachings are still widely discussed and admired even today. Naturally, his death, especially given its murderous circumstances, sent shockwaves across the United States and the world as a whole. In a decade that had seen so much turmoil, Dr. King was a constant figure of enlightenment and progress, which made it all the more devastating. This was the news story a young George A. Romero heard on his drive to New York City that night. Immediately it made his film more relevant and poignant that he could have anticipated.

How It Changed Romero’s Film

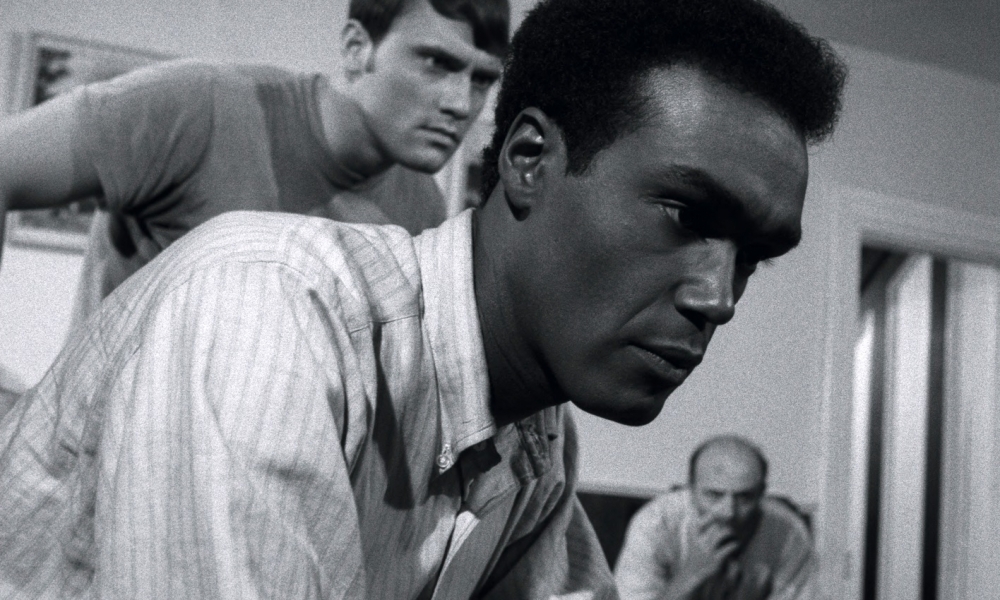

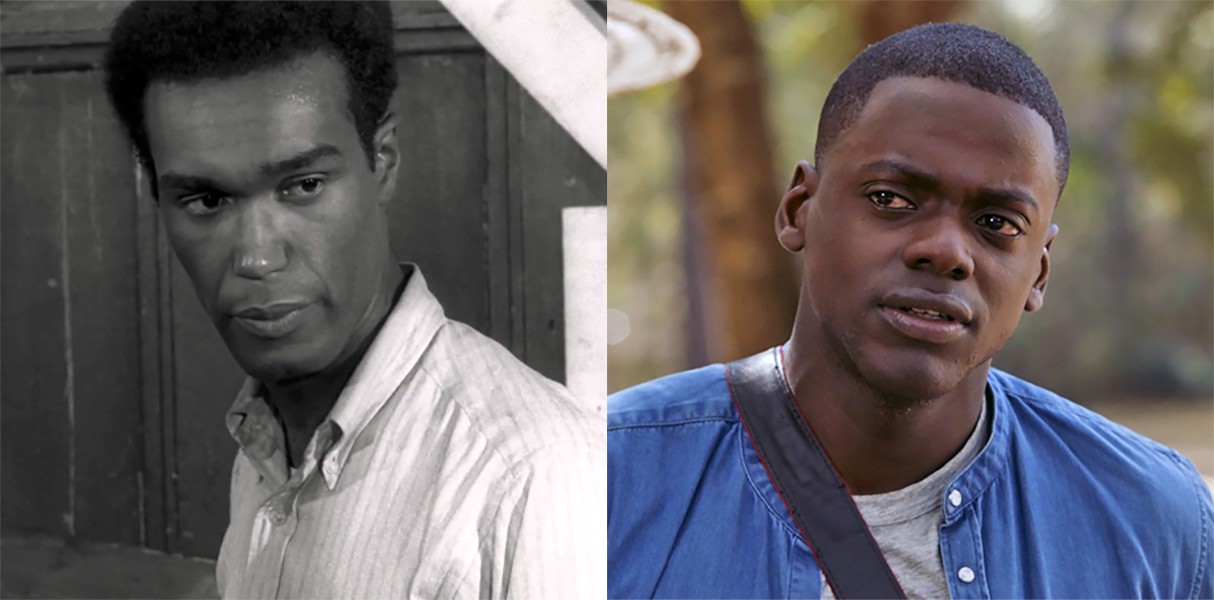

The main character in Night of the Living Dead was portrayed by an African American actor named Duane Jones. At the time of casting, Romero hadn’t given much thought to the race of his protagonist. In fact the script describes the main character as a trucker with anger problems. But Romero was so impressed with Jones’ audition, along with his dignified demeanor, that he changed the character to fit the actor. He thought a level-headed African American man would make for a good leader of survivors in a zombie apocalypse.

In addition, the rather bleak ending resonated with audiences in the wake of King’s assassination. Jones’ character manages to survive until the very end of the film, fighting off the undead as they attempt to penetrate the house he and the other survivors have barricaded. Yet, unfortunately for him, he is gunned down by a police officer when they enter the scene to save the day, because the officer assumed he was one of the undead and took a shot. While Romero merely wrote this ending for shock value, it now had taken on a much greater meaning. Audiences saw Romero’s ending as a political statement and commentary on race relations, and the tragic fate of Dr. King. Because of this, Night of the Living Dead rose from obscurity and became one of the most popular films of the year, as well as jumpstarting a new zombie subgenre of horror.

Romero’s Legacy and Social Commentary

Despite that fact that the symbolism in his first film was purely coincidental, Romero was not lost on the effect Night of the Living Dead had on society. From this he saw a way to make horror films that were both entertaining, but also intelligent with a voice of their own. His subsequent “Dead” films were infused with some form of political and social interpretation. In Dawn of the Dead from 1978, the zombies are portrayed as mindless victims, with an innate desire to congregate near the mall. This was Romero’s critique of commercialism and consumerism, which had skyrocketed in the 1970’s during the age of the shopping mall.

Years later in 2005, he would direct Land of the Dead, which demonstrates a fascist society run by a dictator who keeps his people behind walls so they may be “safe” from the zombie threat outside. This shows eerie parallels the War on Terror of the 2000’s, and the fear of giving up freedom for security in the surveillance age. This is even present in Creepshow, Romero’s collaboration with Stephen King from 1982. One of the vignettes portrays a white man living in a city skyscraper overrun by cockroaches which he fears will consume him, which was always meant to represent his fear of minorities while living in the city.

The Loss of the Legend

George A. Romero passed away on July 16, 2017, and his most recent film Survival of the Dead, came out way back in 2009. His permanent absence is certainly being felt by the horror and filmmaking community. With his body of work, he demonstrated that a horror film can be smart, and not just cheap blood and gore effects without substance. One needs look no further than the current most popular iteration of the zombie subgenre, AMC’s The Walking Dead. Romero himself, while he was still alive, criticized the show by stating it was nothing more than “a soap opera with zombies”. And he had a valid point. The show has droned on for 8 seasons, essentially recycling the same plot points over and over. It has all the action, suspense, and gore as Romero’s films, but lacks the symbolism and wit. It merely challenges its viewers to guess who will be killed off next, rather than challenge them to question some aspect of society. We need more filmmakers like Romero. Filmmakers who can produce well-made horror that satisfies fans of the genre, but that also can be taken seriously because it truly has something to say.